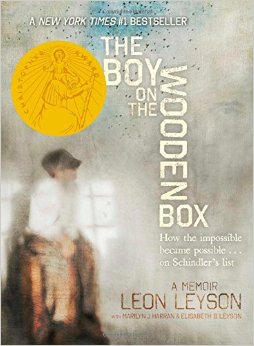

The Boy on the Wooden Box

How the Impossible Became Possible…on Schindler’s List

A Memoir by Leon Leyson

What is the power of one? What can one human being do to “stand up to evil and make a difference”? Leon Leyson gives us his answer to that question in The Boy on the Wooden Box (2013) published by Simon & Schuster. With Marilyn J. Harran and Elisabeth B. Leyson, Leon Leyson has written a moving memoir which tells of his life as the youngest survivor of the Holocaust from Schindler’s list. To Leyson, Oskar Schindler was that one who made the difference between life and death for himself, several of his family members and over a thousand other Jews.

The Boy on the Wooden Box is a Young Adult book (10 years and up) which was a New York Times best seller and received a Christopher Award in the Books for Young People category in 2014. One might consider this book comparable to the fiction novels The Boy in the Striped Pajamas (2006) by John Boyne, or The Book Thief (2005) by Markus Zusak, but The Boy on the Wooden Box is non-fiction, and carries the weight of reality in its detailed stories and descriptions of the Nazi plans to “cleanse” the Jews from Poland. In addition to writing his memoirs in The Boy on the Wooden Box, Leon Leyson, who died on January 12, 2013, video-taped his story as a Jewish Survivor for the archives of the University of Southern California Shoa Foundation, and spoke to countless organizations about his experiences of living through the Holocaust.

Leon Leyson, whose Hebrew name was Leib Lejzon, was born in the village of Narewka, Poland on September 15, 1929. The Boy on the Wooden Box starts with happy memories of Leib’s early childhood in Narewka among his extended family and Jewish community. In 1938,when he was 9 years old, Leib’s father’s work required that the family move to the city of Krakow, about three hundred miles away. Not long after their relocation, the Germans invaded Poland. Leyson writes, “It was September 6, 1939. Less than a week after crossing the border, the Germans were in Krakow. Although we didn’t know it, our years in hell had begun.”

Leyson shares his 10 year old perception of the downward spiral of the lives of the Jews in Krakow, and his confusion as little by little, the Jewish community was stripped of every basic right, even down to the ability to own a bike or radio.

Leib also describes his fears as their lives were divested of predictable daily routines, including attending school, and he tells of his small, individual efforts to resist the new way of life being forced upon the Jews. He writes that he was intrigued by the German soldiers in his town. It was 1940, a time of relative freedom for Jews to move about the city of Krakow, and Leib was under twelve years old, which meant he did not yet have to wear an arm band that marked him as a Jew. Since he spoke German and did not “look” like a Jew, Leib decided to talk to the young German soldiers guarding a petroleum tank across the street from his family’s apartment. Leib knew the German soldiers could change from friendly to violent in an instant, but he was bored and curious. He visited with the soldiers several times, even going into the guard station with them and sharing in their chocolate rations at times.

Then one night, as he was sleeping, “[the soldiers] grabbed me out of bed by the hair.

“‘What’s your name?,’ they shouted. ‘Are you a Jew?’

“I replied that I was. They slapped me, furious that they had assumed I was a “normal” kid. Fortunately they didn’t take the abuse beyond their slaps and abruptly left our apartment. I ran into my mother’s arms shaking and crying…” Soon Lieb’s family, and thousands of other Jews, would be moved out of Krakow to a ghetto town designed for them by the Nazi’s, but before they moved to the ghetto, Leyson writes, his father performed a highly technical service for a Nazi business owner. That Nazi happened to be Oskar Schindler, and because of the expertise of Lieb’s father, Schindler hired him to work in his enameling factory. Leyson writes this about Schindler:

“Oskar Schindler has been called many names: scoundrel, womanizer, war profiteer, drunk. When Schindler gave my father a job, I didn’t know any of those names, and I wouldn’t have cared if I had. Krakow was filled with Germans who wanted to make a profit from the war. Schindler’s name meant something to me only because he had hired my father… [and] working for Schindler meant that my father was officially employed. It meant that when he was stopped on the street by a German soldier or policeman who wanted to grab him for forced labor, to sweep the street or haul garbage or to chop ice in winter, he had the necessary credential as protection…[Father had a work document which] was a shield of protection and status. It didn’t make him invincible to the whims of the Nazi occupiers, but it made him a lot less vulnerable than he had been when he was unemployed.”

Eventually, as the story of The Boy on the Wooden Box relates, all four remaining members of Lieb’s family are employed by Schindler, are put on Schindler’s “list” and will survive the Holocaust. Recalling his time in the factory, Leyson writes about how Schindler would come over to his machine, “Tall and hefty, with a booming voice, he would ask me how I was doing….He looked me in the eye, not with the blank unseeing stare of the Nazi’s, but with genuine interest and even a glint of humor. I was so small that I had to stand on an overturned wooden box to reach the controls of the machine. Schindler seemed to get a kick out of that.”

Because of Schindler “the impossible became possible” for Lejzons. Did this mean that the Lejzon family was spared the atrocities and horrors of the prison camps? Not in the least. Leyson’s book depicts clearly the inhumane treatment, pain, and starvation that were a constant presence, and shows that death was a daily possibility for everyone in the Nazi prison camps. But, “Despite impossible odds,” Leyson writes, “we…made it.”

Leyson tells of the shock and joy he felt at the end of the war when he saw the German officers and soldiers fleeing. By this time the entire population of prisoners knew the Soviets were rapidly approaching the prison camp, and their freedom was at hand. Schindler understood the danger he was in as a Nazi and that he had to leave, but he chose to say goodbye to the Jewish prisoners before he drove away. Leyson was with all the others when they presented Schindler with a ring made from a prisoner’s gold tooth. The ring was inscribed in Hebrew with the Talmudic saying, “He who saves a life saves the world entire.”

Leyson does a superb job of telling about his and his family’s painful yet miraculous ability to hold on to life throughout the Nazi’s attempts to exterminate the Jews. Leyson states his purpose for sharing his story in The Boy on the Wooden Box is to be certain that one man’s part in their survival, the part played by Oskar Schindler, is neither diminished nor forgotten, and to remind every person who reads The Boy on the Wooden Box of the power of one.

thyrkas