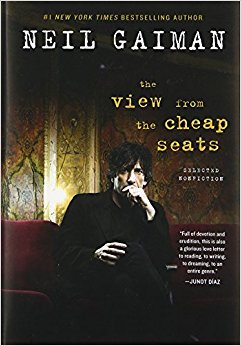

The View from the Cheap Seats

By Neil Gaiman

–Review by Paula Jones

Neil Gaiman’s writing can be a lot like coffee. You have to develop a taste for both, but in doing so, both will eventually grow into a craving. When first introduced to his work, I was only mildly impressed, but because my daughter and niece both adore him, I continued to read. These days, I anticipate his new publications with eagerness, so much so that I purchased The View from the Cheap Seats (TVFTCS) the day it debuted.

Gaiman is known far-and-wide for the fantasy novels and graphic novels for which he has received 67 prestigious writing awards. In 2010, he became the first author ever to win both the Newbery Medal and the Carnegie Medal for the same work (The Graveyard Book). That said, TVFTCS, being 100% non-fiction, is not his typical fare. Considering that Gaiman began his career as a journalist, this is obviously not his first foray into non-fiction. In the years since those early days as a reporter, he has since written numerous forwards to republished science fiction classics, countless keynote addresses for various writer and reader conferences, multiple eulogies for other writers, and even several introductions to albums. TVFTCS is a compilation of many of these short addresses and essays.

As one reads through it, they find themselves knee-deep in a class on the history of fantasy, science fiction, and graphic novels. They also find themselves discovering the man Neil Gaiman as he divulges his innermost thoughts while describing the events, the people, and (most of all) the books that have influenced his life and style. In his 2012 commencement address at University of Arts in Philadelphia (included in TVFTCS), he states, “That moment that you feel that, just possibly, you’re walking down the street naked, exposing too much of your heart and your mind and what exists on the inside, showing too much of yourself, that’s the moment you may be starting to get it right.” If that is true, Gaiman got it right. TVFTCS can almost serve as his autobiography, yet in writing it, he somehow manages never to direct undue attention to himself.

TVFTCS is divided into ten sections with each section revolving around a uniting theme. For example, one is comprised of his musings on comic books; one consists of his thoughts on fairy tales; one is a group of eulogies for writers who have influenced him, and one portion is composed of the forwards Gaiman has written for reissued science fiction books. On the positive side, I have added several of his favorite books to my imaginary bookshelf stocked with must-reads. On the negative side, although each essay is a work of word-art in itself, there are only so many introductions and eulogies one can read without beginning to yawn. Unless one is a devoted fan of mid-to-late twentieth century science fiction, the book bogs down in several sections.

That said, the first section of the book is exquisite. In its eleven short chapters, Some Things I Believe is practically a song of praise to books of fiction and their temples (public libraries). In it, Gaiman verbalizes a trusism known to every avid reader who first discovered the addictive power of a good book as a child, “Fiction is a gateway drug to reading.” He rhapsodizes about the value of libraries and waxes lyrical about the power of imagination. Defending ‘escapist’ fiction, which is often looked-down on as inferior to the expository style of non-fiction, Gaiman writes:

If you were trapped in an impossible situation, in an unpleasant place, with people who meant you ill, and someone offered you a temporary escape, wouldn’t you take it? And escapist fiction is just that: fiction opens a door,

shows the sunlight outside, gives you a place to go where you are in control, are with people you want to be with (and books are real places, make no mistake about that); and more importantly during your escape, books can

give you knowledge about the world and your predicament, give you

weapons, give you armor; real things you can take back into your prison.

Skills and knowledge and tools you can use to escape for real. As C.S.

Lewis reminded us, the only people who inveigh against escape are jailers

. . . Sometimes fiction is a way of coping with the poison of the world in a

way that lets us survive it.

In places, Gaiman writes as the consummate storyteller giving advice to other storytellers, using his own experiences while informing them how to ‘get it right.’ Although TVFTCS is primarily focused on writers of fiction, much of its advice is just as applicable to the work of the person who tells the stories of scripture or writes sermons. For example, when it comes to telling fairy tales he remarks, “Like any form of narrative that is primarily oral in transmission, it’s all in the way you tell ‘em.” How many people might have grown to love Bible stories if they were told with the enthusiasm and the sense of suspense that they deserve? Consider these other tidbits: “Truth is not in what happens but in what it tells us about who we are. Fiction is the lie that tells the truth, after all,” “We have an obligation not to preach, not to lecture, not to force predigested morals and messages down our reader’s throats like adult birds feeding their babies premasticated maggots,” or “The world doesn’t have to be like this. Things can be different.” Is that not the very essence of, “Thy Kingdom come. Thy will be done?”

As with his other writing, Gaiman’s words in TVFTCS are simple. He never wastes them. His style is unpretentious, filled with metaphor, and never draws attention to itself. His advice to the many writers in his audience is not only spot-on, it is also future- focused. In the chapter Business as Usual, During Alterations: Information Doesn’t Want to Be Free, Gaiman paraphrases a metaphor once used by Cory Doctorow to shed light on the enormous changes in publishing now that we’ve entered the age of the internet:

Mammals . . . invest a great deal of time and energy in their young, in

the pregnancy, in raising them. Dandelions just let their seed go to the

wind, and do not mourn the seeds that do not make it. Until recently,

creating intellectual content for payment has been a mammalian idea.

Now it’s time for creators to accept that we are becoming dandelions.

Perhaps this is a metaphor the preacher needs to ponder as wel