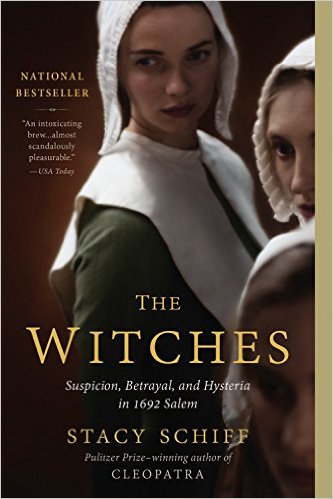

The Witches: Suspicion, Betrayal, and Hysteria in 1692 Salem

By Stacy Schiff

–Review by Paula Jones

My love for good history books developed as a young adult, and only because first-rate historical fiction eased that door open. While Pulitzer Prize winning historian Stacy Schiff’s The Witches: Suspicion, Betrayal, and Hysteria in 1692 Salem is officially classified as history, at times it seems to slip into the genre of historical fiction. Although tediously researched, it also probes deeply into the emotional states and motives of main players in the tragedy, assuming things that could not be known from the existing written records of court officials and spiritual leaders. As a result, some characters are one-dimensional. Cotton Mather becomes a caricature of a dour Puritanical preacher, local magistrate John Hathorne an incompetent prosecutor doggedly pursuing a pre-ordained conclusion, and high sheriff George Corwin a corrupt, opportunistic, contemptible person.

Her book is nevertheless a compelling read. As an unquestionably gifted storyteller, Schiff offers such vivid descriptions of life in 1692 that it makes one wonder if she might herself be benefiting from a little witchcraft. Has she perhaps time traveled? Spoken to spirits? Signed a pact in blood for insider knowledge of weather, domestic tensions, and the agonies of living in an overcrowded, underground dungeon for months on end?

Fourteen women, five men, and two dogs––yes, two dogs––were executed as witches. More than 400 others were accused, and a coven of 700 were rumored to be meeting in a nearby field, this in spite of the fact that “the population of New England in 1692 would fit into Yankee Stadium today.” Every single person tried for witchcraft was found guilty and sentenced to die. Others died in jail where dozens were forced to live in cramped conditions––manacled with iron in an underground, unlit, unventilated, leaky stone dungeon with no toilet facilities or heat––through a bitterly cold winter. At least one woman gave birth born in this cruel setting.

Schiff labors to make each accused ‘witch’ memorable in his or her own right, permitting them to stand out as a distinct individuals in a community that was determined to rob them of their humanity. Seventy-one year old pillar of the community Rebecca Nurse begged for mercy, not for herself but for others on trial. Harvard educated Reverend George Burroughs rode to his death with immense dignity in a crowded horse-drawn wagon, praying for the other 4 who would soon hang with him. His last act was to forgive his accusers, the trial judges, and the jurors. Until their own arrest, John and Elizabeth Proctor were outspoken critics of the trials, zealously defending the accused and writing to Boston clergy asking them to intervene in the madness. Five-year-old Dorothy Good spent more than eight months shackled in the dungeon. Forced to testify against her mother who hanged afterwards, she went insane. Schiff forces us care about each victim.

Perhaps Schiff’s most attention-grabbing addition to the many books examining the Salem trials is her surreal writing style. Never making a distinction between the real and the imaginary, she embraces all information as if it were equally valid. One minute, she is matter-of-factly describing court proceeding or the Puritan religion. The next Schiff is presenting the deadly serious testimony of a witness who sees ghosts flitting about the rafters of the courtroom or another who insists he is visited nightly by one of the witches who is chained in the dungeon. The reader is left to decide what is or is not real. Only occasionally does editorial enter her writing, and then in the form of humor or sarcasm in statements such as, “The only brooms that played a role in the witch hunt were wielded afterwards by men to sweep the year under the carpet,” or, “The fear of Baptists seemed as ingrained there as that of Indian ambush.”

It becomes clear that the original accusations were made individuals seething with resentment. Teenage servant girls accused harsh (possibly abusive) masters. Citizens involved in property disputes accused their rival neighbors. Husbands accused nagging, irksome wives. One man, Thomas Putnam, was responsible for initiating nearly half the charges. The accusation of witchcraft “provided a means to eradicate all malignancies at once.” The denunciations may have begun as a means of retaliation, but embellished with apocalyptic overtones by clergy, revenge rapidly ripened into mass hysteria that destroyed lives, families, and communities. Even after multiple witnesses admitted they had fabricated the allegations, the executions continued.

Within months the insanity ended, but it was too late for many. Those still in prison were released, many with ruined health, some insane, and all impoverished; while in jail, their material possessions had been confiscated, never to be returned. Children were left orphaned and homeless. Those fortunate enough to have survived the madness did so as social pariahs. “Like an internet rumor gone viral,” the label witch was never forgotten by their neighbors.

Schiff goes into great detail explaining the who, what, when, and how of Salem. She never attempts to give a definitive why. The most popular theories include hysteria from the stress caused by threat of attack from nearby Native Americans, an outbreak of encephalitis lethargica, or even eating rye bread that contained the fungus from which LSD is made. Schiff’s best explanation includes a trio of factors: 1. People had agendas. 2. People had convictions that became obsessions. 3. People were genuinely afraid.

Mass hysteria occurs when a group falls into a collective delusion grounded in fear, and fear does strange things to people. Imagine the panic if someone screamed, “He’s got a gun!” on an airplane. The earliest settlers of New England firmly believed in witches. Already under constant duress trying to survive in a harsh and unforgiving land, fear overwhelmed them. When a group of teenage girl shrieked, “Witch!” at the adults they resented (and what teenager does not resent adults), a fuse was lit. Superstitious adults that could have extinguished that fuse instead panicked. When it detonated, the implosion reverberated in accusations in 25 nearby towns.

Unfounded accusations continue. Today they often take the form of fake news stories that play to our basest fears. During the recent election, the internet exploded with politicians and pundits yelling, “Witch!” in one way or another. As Christians, perhaps we need instead to take the life-affirming directive of Jesus to accept his proffered peace instead of bowing to flames of fear. It is He who said to his disciples, “Do not be afraid.” “Follow Me.”