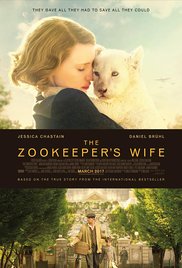

The Zookeeper’s Wife, starring Jessica Chastain, Johan Heldenbergh, Daniel Brühl

–Review by Ashley Linne

This film is rated PG-13.

The Zookeeper’s Wife is based on the lesser-known true story of the keepers of the Warsaw Zoo, who saved hundreds of Jews during World War II. When the Germans occupied Poland, Antonina Żabiński and her husband, Dr. Jan Żabiński, found a way to covertly use their zoo to protect and transport Jews to safety. After the war ended, the Warsaw Zoo was rebuilt and remains open to this day.

Notably, this holocaust film is directed by a woman and features a strong female lead. As some reviewers have pointed out (see Jacob Soll’s review: https://newrepublic.com/article/141806/revelatory-horror-zookeepers-wife), the director took a slightly different take on the holocaust atrocities than most films in this genre, by highlighting brutality of women, children, and animals. We see crimes like these happening across the world at pretty much any point in time. If you removed the film from its context of WWII, parts of it could have been about any war or even a current events piece.

I noticed before I viewed the film that it was getting some mixed reviews. Some reviewers seem to feel the story wasn’t told with as much impact as it could have had been. I wonder if this is partially because the film is not full of shocking levels of gore. Obviously, our culture has become desensitized to depictions of violence and is conditioned to seeing it in extremely realistic detail. I, for one, appreciated that this film seemed to strike a balance in this regard, conveying disturbing truths without becoming overly graphic. To be sure there is disturbing material presented, so viewers should be aware of this. But it wasn’t taken to the degree it could have been.

From a semiotic standpoint, there are a couple of scenes where overt sign-reading is apparent—Jan tells Antonina they will have to hide in plain sight; the main Nazi character, Hitler’s zoologist Lutz Heck, sees the signs of Jewish resistance in a bakery and has it burned to the ground; Lutz discovers the signs of Jews being saved throughout the underground passages of the zoo. There isn’t an abundance of semiotic nuance, but again, the fact that the story is told from a woman’s perspective makes the film semiotically unique. Frequently Antonina’s character is silent or doesn’t say much (I’ve read some critiques of the script in this regard), but I had no trouble knowing what was going through her mind in those scenes.

I want to be careful not to commit cultural appropriation here, or to take away from the fact that this is primarily a film about antisemitism. But as a woman, I felt a connection to Antonina and I imagine many women would, no matter our ethnicity or religious background. Most women can identify with Antonina’s compassion and strength, and that she wasn’t trying to be a hero but was simply doing what she had to do to protect life. Most women probably know what it is like to feel trapped into a game of sorts with a man who has power over us, like Antonina’s precarious relationship to Lutz. Many of us too perhaps have felt the shame of having to “play along” with men like that in order to save ourselves or someone we love.

I had reservations about presenting this film review the week of Passover and weekend of Easter, but in a way, it seems appropriate now. The Story of the Resurrection was heralded by women—women who didn’t set out for notoriety that Sunday morning, but who were simply doing what needed to be done and encountered the Risen Savior along the way. Jesus gave those women a Story to tell, and He acknowledged their dignity and worth as women and witnesses. May we all, men and women alike, open our hearts to follow the work of the Spirit as He seeks to rescue His people, and to do so with humility and grace.