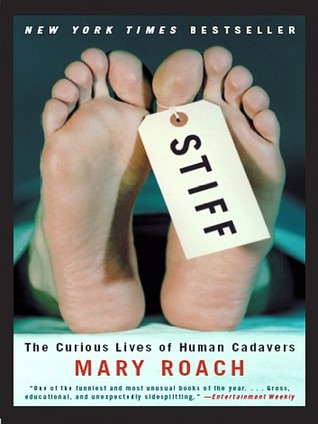

Stiff:

The Curious Lives of Human Cadavers

by Mary Roach

“Treat the living as though they were dying, and the dead as though they were alive.” Russian philosopher Nicholas Berdyaev (1874-1948)

Stiff: The Curious Lives of Human Cadavers by Mary Roach (W. W. Norton & Co., 2003), is an unusual book. It is a non-fiction, science-related publication about dead bodies written by someone who does not have a formal background in science but who does meticulous journalistic research for her stories. And although the subject of death and what happens to the body after death is a morose topic, Mary Roach has managed to mix in plenty of quirky, laugh-out-loud humor. The resulting product of her fact-finding mission about cadavers and her humorous style of writing is a surprisingly enjoyable book about an uncomfortable, unavoidable subject.

Cadaver research is not the only oddball topic that Roach has found to write about in her award-winning career. Some of her other books are: Grunt: The Curious Science of Humans at War; Packing for Mars: The Curious Science of Life in the Void; and Spook: Science Tackles the Afterlife. Roach has also written for various magazines, including Salon, National Geographic, New Scientist and the New York Times Magazine. In addition, the author has a website which, fittingly, has an animated line-drawing of a roach crawling up the screen of the homepage. http://maryroach.net/books-news.html. Roach’s most recent publication, Gulp: Adventures on the Alimentary Canal, was shortlisted for the Royal Society Winton Prize for Science Books of 2014.

There are many cadaver-related subjects to explore in Stiff, but one of the most interesting is “Crimes of Anatomy.” In this section Roach first describes the respect shown the cadavers of the anatomy labs at the University of California, San Francisco, Medical School. Especially moving is the recounting of a memorial service for the remains of the bodies used for dissection. Roach writes, “This [service] is no token ceremony. It is a sincere and voluntarily attended event, lasting nearly three hours and featuring … student tributes…”

But Roach continues: “To understand the cautious respect for the dead that pervades the modern anatomy lab, it helps to understand the extreme lack of it that pervades the field’s history. Few sciences are as rooted in shame, infamy and bad PR as human anatomy…The trouble began in Alexandrian Egypt, circa 300 B.C…”

From his royal throne in Egypt, says Roach, King Ptolemy was the first leader to promote the value of opening the human body for educational purposes. “In part this had to do with Egypt’s long tradition of mummification,” we read. But mummification was not practiced in all areas of the world, which meant that access to bodies for the purposes of study was a big problem for students and practitioners alike, and it remained a big problem for centuries. History demonstrates that religious and civil laws governed what could be done to and with a corpse. In the West, says Roach,” [The] only cadavers legally available for dissection in Britain were those of executed murderers.” Still, there were any number of people who were willing to go outside the law to obtain cadavers — for a price. Grave robbers, also called “resurrectionists,” made good money in Britain until the passage of the Anatomy Act in 1836.

For many generations of students in the health sciences, gross anatomy courses have not just been about learning what the body looks like below skin level, they have also been about confronting the reality of death. As far as the present need for whole cadavers for the purpose of education about death Roach says this: “Modern educators feel there are better, more direct ways to address death than handing students a scalpel and assigning them a corpse. In…anatomy class at UCSF, as in many others, some of the time saved by eliminating full-body dissection will be devoted to a unit on death and dying…”

At some point, most of us will have to make a decision about what to do with our bodies after death. In Stiff, Roach has researched several options relating to what one might chose to do with one’s remains. There is, in the US, the most traditional choice: embalming the body and then burial in a casket at a cemetery. This is a time honored method, most often associated with formal church services, flowers and ornate caskets. But Roach writes, since “1963 — when the Catholic Church in the wake of the reforms of Vatican II, relaxed the ban on cremation– [disposal of remains] by incineration would take hold in a serious way.” Roach notes that 1963 was a banner year for cremation due to the publication that summer of The American Way of Death, “the late Jessica Mitford’s expose’ of deceit and greed in the burying business.”

Roach also includes in Stiff stories about funeral reformers, most of whom have had a tough time introducing changes to the funeral industry and to the public. Presently there are several burial alternatives that are becoming more mainstream in the US, and Roach writes about each of them at some length. The author points out that in years past, it was primarily Church authorities who determined what the correct means were for laying a body to rest with dignity. In more recent history, the funeral director has often had the final say in how a funeral should be conducted. Currently, it is the family of the deceased that makes important burial and funeral decisions.

One burial alternative is not particularly new: the donation of one’s body to science. Roach is detailed in her research on this matter and includes several chapters that describe various institutions that use cadavers and the types of research done. She informs the reader of the difference between being an organ donor for transplant, which she strongly recommends to all, and the giving of a body to science. Roach also includes the particulars on how to go about making a whole body donation and offers some honest but humorous advice to those who are genuinely considering this choice: “You can’t specify what you are used for; you go where there is a need. The majority of willed bodies wind up in the anatomy department. Almost none end up in the English Department. Medical conferences where surgeons practice new techniques are a common venue. If there is something you would rather not be used for, make this clear on your donor form or in an attached note. Have fun!”

Stiff: The Curious Lives of Human Cadavers by Mary Roach is a book that will grab your full attention. Roach treats her subject respectfully 99% of the time; I think she goes over the top in some chapters, but not enough to make me back away from the book. Roach also uses her comedic timing to great advantage, providing frequent comic relief from the first to the last chapter. Stiff is an unconventional and fascinating book that, in a paradoxical way, reveals a lot about the living; especially how we think of and deal with our dead.