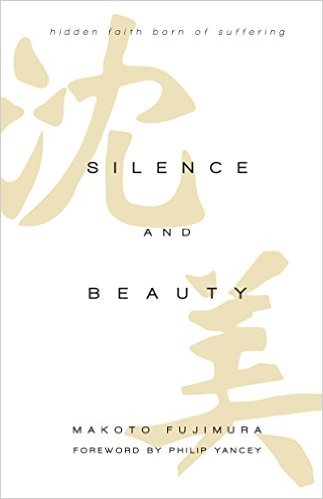

Silence and Beauty:

Hidden Faith Born of Suffering

by Makoto Fujimura

The role of a gifted artist with an educator’s skill and a unique understanding of a difficult subject is the mantle that Makoto Fujimura has assumed in writing the book Silence and Beauty: Hidden Faith Born of Suffering (InterVarsity Press, 2016). Silence and Beauty is Fujimura’s amazingly insightful response to Silence, the stark and disturbing novel by Japanese Christian writer, Shusaku Endo (1923-1996). Fujimura is a traditionally trained Japanese-American visual artist who had a bi-cultural upbringing between the US and Japan. He is also a Christian. Because of these influences on his life, he is able to respond to and evaluate Endo’s work from an unparalleled vantage point. Fujimura shares his illuminating views on Endo’s writing, and on the Christian life, in Silence and Beauty.

Fujimura was a National Scholar at Tokyo University of the Arts pursuing his study of Japanese aesthetics when he first came upon a collection of art objects known as fumi-e at the Tokyo National Museum. On exhibit were display cases full of the flat, tablet shaped objects from seventeenth-century Japan. Fumi-e, which translates literally as “stepping blocks,” were made to be used during the time of persecution of Christians in Japan (1614-1873). Fujimura writes, “[Fumi-e] are images of Jesus, or the Virgin with a child, carved on wood or cast in bronze. Villagers were asked to…renounce Christianity by stepping on these blocks.” If the individuals did not step on the fumi-e they were jailed and tortured, and many were martyred. Fujimura goes on to say, “I had just come to embrace faith in Christ at the age of twenty-seven after several years of spiritual awakening. Now I faced, literally, the reality of Christian faith in Japan.”

It was after his encounter with the fumi-e that Fujimura read Endo’s Silence, the troubling story of a Catholic priest in Japan during the time of the persecution, who, after many trials, chooses to step on a fumi-e and renounce his faith rather than face torture and martyrdom. Fujimura writes, “Reading Silence…was an excruciating experience, especially as a new believer in the Christian faith.” Fujimura also noted that despite the ordeal of reading Endo’s gruesome novel about the persecution of Japanese Christians and missionaries…”one fact remains jarringly clear… Silence… is proving to be an extraordinarily enduring and generative work of art.”

It is hard to imagine that a book as difficult to read as Silence might offer encouragement to the Christian community, yet throughout Silence and Beauty, Fujimura shows that the “gruesome novel” hides within its pages the seeds of good fruit. One of the many hopeful messages which Fujimura is able to discern in Endo’s story is this: Silence is a Holy Saturday book. “This book,” writes Fujimura, “is about the movement of our souls into Holy Saturday waiting for Easter Sunday. Endo, in many respects, is a Holy Saturday author describing the darkness while waiting for Easter light to break into the world… To Endo, the failure of seventeenth-century missionaries was not the end, but the beginning of another journey toward compassion, a painful gift for all of us.”

Fujimura describes Endo as a novelist of pain, and compares his writing to that of Flannery O’Connor. Pointing out that, “Like O’Connor, Endo writes as both an insider and an outsider. O’Connor is noted for having written in the ‘Christ-haunted South’ as a Catholic, which made her a foreigner of sorts in the Protestant American South even though she was a native of Savannah, Georgia.” Fujimura maintains that, “Endo, too, wrote in a country haunted by Christ, and this historical mark, like the footprints in the wooden frames of a fumi-e, remains indelible…” The period in Japan which followed the edict to ban Christianity was, Fujimura writes, “One of the darkest periods in the history of the Japanese Christian church…The darkness would mar the psyche of the country and define its aesthetic even to this day. This is the wound that Shusaku Endo captures in Silence.“

There is a Japanese aesthetic known as wabi (things worn) and sabi (things rusted) that Fujimura says captures both the essence of a fumi-e and the reality of Christ. “For a Japanese to behold a fumi-e reminds that person of the beautiful, and at the same time casts light on its most improbable source — Christian persecution and, ultimately, the person of Jesus…Japanese aesthetics is therefore linked deeply with the unique imprint of Christ…This counter-intuitive reality — Jesus’ paradoxical power through weakness, beauty through brokenness — is expressed perfectly in the [wabi sabi] surface of a fumi-e.”

The final pages of Silence can lead the reader to believe that the Japanese authorities were successful in destroying Christianity in The Empire of the Sun, but two hundred years of persecution did not drive Christianity out of Japan; instead, it drove the Japanese Christian community underground. In 1865, seven years after Japan again opened its doors to foreigners, a visiting priest who was serving a parish near Nagasaki discovered a group of Christians. Fujimura writes that they were called ‘Kakure Kirishitan’ (Hidden or Hiding Christians). He goes on to say, “Remarkably, they maintained their faith and rituals generation after generation, praying to a hidden altar or creating what seemed to be Buddhist statues but were actually the Virgin and Child, and they practiced communion with sake and rice chanting vague references to the Bible in what over centuries became an unrecognizable dialect that combined Latin, Portuguese and Japanese.”

In Silence and Beauty Fujimura sees the existence of the Kakure Kirishitan in Japan as evidence that “faith can include failures, even multiple failures…God embraces us, just like the father in the story of the prodigal in Luke 15, despite our many sins of omission…Faithful presence can reverse two centuries of indentation left by persecution, and contribute to the healing of the wounds of the Japanese. I ultimately believe that this presence is what Shusaku Endo desired to depict in his book and not the ‘silence of God.’ “

Makoto Fujimura spent twenty five years considering Endo’s book Silence, which finally culminated in his book Silence and Beauty: Hidden Faith Born of Suffering. He says, “Writing this book serves as a testament to me of God’s greater purpose of revealing Christ to me in Japan: I was to find Christ through the image of fumi-e and to write and wrestle with Endo’s great work, connecting his language to the beauty of seventeenth century Japan. It takes time to realize the fulfillment of the seed sown into our creative hearts. Such is the power and the magnetism of Endo’s masterpiece, sown into the hearts of all people seeking refuge from trauma in Endo’s art of brokenness.”

Certainly for anyone interested in Shusaku Endo’s Silence, Fujimura’s Silence and Beauty is an invaluable companion book. The wealth of understanding Silence and Beauty offers is a grace gift to the reader, as well as a powerful means of uncovering the hope hidden within Endo’s Silence.