The Home Stretch

Lectionary

14 April 2019

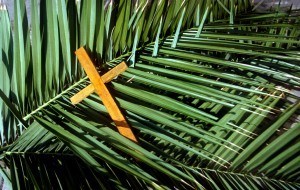

Palm Sunday / Passion Sunday

Luke 19:28-40

Psalm 118:1-2, 19-29

Isaiah 50:4-9a

Psalm 31:9-16

Philippians 2:5-11

Luke 22:14-23:56 or Luke 23:1-49

Text to Life

Who doesn’t like a party??!!

We all love “Palm Sunday” because of the parade of pomp and pageantry that accompanied Jesus as he entered into Jerusalem for that final time in his earthly ministry. It was a party, right? There were crowds. There was singing and dancing. There was shouting and cheering-—with Jesus riding through the gates of city, which we often call his “triumphal” entry in Jerusalem.

The people gathered along the roadway from Bethlehem to the Sheep Gate, but let’s be clear about where Jesus was going. The crowds were excited and expecting this procession to end in some great show of power and might, and maybe even miracles. But let’s be clear where they were headed. Once a lamb was brought through that gate for sacrifice, there was no way out. There was no way back. The gate on the north of the city, this one opening in the ancient walls of Jerusalem through which lambs were brought for sacrifice, was a one-way street. As it was now for the Lamb of God. It is theologically significant that Jesus first identifies himself, not as the Good Shepherd, but as the Sheep Gate, the gate for the sheep.

The lectionary readings for this week give preachers a choice of either the “Palm Sunday” texts or the “Passion Sunday” narrative. Overwhelmingly congregations hear about the palm-studded, cloth carpeted processional of Jesus’ entry into Jerusalem. The “Passion Sunday” scriptures are not so rosy. These are the texts that describe what happened to Jesus after he made that no-exit grand entrance into the city.

The Passion of the Christ is not a celebration. It is not a manifestation of power, at least how we understand power. It is not a moment for miracles, at least how we usually define miracles. This week’s “Passion Sunday” texts from Luke tell the terrible, terrifying tale of Jesus being hauled before the highest officials in the territory, being interrogated about his identity and mission, and being hung out to dry by weak-kneed, washed-hands government officials and politicians of the faith who viewed Jesus as a threat to the reigning “status quo” that kept in check the Roman rulers and religious leaders so that the interests of both were balanced out.

If you read all the biblical texts that are “assigned” for “Holy Week,” you do read the story of the passion of Christ, with all of its drama, all of its heights of turmoil and depths of tragedy. But if you only attend on “Palm Sunday” and hear about Jesus’ triumphal entrance into Jerusalem, and then attend Easter Sunday services celebrating the resurrection of the Christ, you miss the important stuff. You know, the “stuff” that is typical human behavior that makes Jesus’ crucifixion necessary. The “stuff” that makes his resurrection such a miraculous redeeming gift for all of creation. The “stuff” we used to acknowledge as the fatally broken relationship creation had with God. Short-cut I.D. for this terminal condition: sin.

In the early church, they celebrated Lent and Holy Week quite differently. In the earliest days of the church, where discipling in the way and walk of Jesus was paramount, the “Passion of Christ” was not an alternative “choice” of scripture reading. It was the focus of the entire discipleship journey.

In the early church baptism was not something you “scheduled” to accommodate the grandparents’ travel plans. Baptism was a three-year faith journey that was designed to transform a “convert” into a “disciple.” The journey from “believer” to “disciple” was not a text-based, doctrinal study of church teachings. It was instead a mentor-apprentice hands-on, heart-centered, spirit-driven “education” in faith practices, prayers, and missions.

In the late twentieth century, educational reformers insisted scholarly studies include besides classroom learning what is called “praxis”—a fancy name for “practical experience.” Whatever the discipline, a student was expected to integrate “praxis” into theory. Of course, doctors and lawyers and architects had that kind of “learning curve” in place long before the educational reformers came on the scene. As part of their “professional” education practical experience is required. Law school students serve as go-fers and do-it-alls in big law firms. They learn by doing what it takes to build a case or construct a defense. Sleep is not always an option. Same with medical school, where students “graduate” with a “Dr.” before their name but are immediately plunged into the bottom of the pool at a medical facility in something humbly called an “internship.” After a year or two of “interning” the “Dr.” gets promoted to a “residency.” It is all basic apprenticeship and mentoring by masters of the craft of healing.

Almost the same was true for early baptismal candidates in the church. Confessing faith in Christ was one thing. Conforming your life to a life of true discipleship in Christ’s way, truth, and life was another. It took years, mostly three years of intense apprenticeship, to root and grow before “baptism,” the “doctoral diploma” would be granted to a follower of Jesus. But your “doctoral diploma” was not granted for your doctrinal mastery. That was a later alteration of the church that moved the discipling journey from catechumen to confirmation, which could take place over a day, a week, a month or any period of time. Not so in the early church.

For our earliest forebears, those three years were not spent reading doctrines or learning languages. Those years were spent being schooled by master disciples of Christ into what it meant to be a follower of the Way, Truth, and Life. As a baptismal candidate you learned to read the Scriptures as Jesus had read the Scriptures—which often was with a distinctly different interpretation. Disciples “in training” were taught to reach out to the poor, just as had Jesus. Disciples “in training” were taught to reach out and offer healing to the sick, just as had Jesus. Discipleship training for those hoping to be baptized was all about practicing the faith in a faith community of practice. Your apprenticeship was less in “knowledge” as information than in “knowing” Jesus personally by doing the things he Jesus did and going the places he did. Like the prisons. Like the poor. Like the diseased and deformed. Like the children. Like the elderly and abandoned.

After a three-year period of intense training called “catechesis,” wannabe disciples called “catechumens” would enter the “homestretch.” This was the third Lenten period just before Easter. Your homestretch as an apprentice ENDED on Palm/Passion Sunday. Palm Sunday is the end of Lent. This Sunday Lent is over. We as a faith community have moved into a new season in our faith calendar. It is now the beginning of Holy Week. Lent is done. Holy Week has begun.

For apprenticing disciples in the early church this meant it was finally the end of their “catechumenate,” their period as “interns” or “apprentices” or “catechumens.” Holy Week was the time when they relived in all its intensity the high and holy moments in Jesus’ last days in preparation for that high and holy rite of initiation they had prepared so diligently and devotedly to receive in all humility and integrity: baptism. The Homestretch of Lent was a final crash course in the core stories and key practices of Jesus’ mission. Holy Week was when the apprentices fixed their mind, body and spirit on his last days, ending with the Great Vigil, his resurrection. This was the real party, when no stones were left unturned, to celebrate and lionize the Lamb’s victory over sin and death.

Palm Sunday is all about a celebration. Passion Sunday is all about the realization that followers of Jesus must dedicate themselves to something more than a “party.” And they both happen on the same Sunday. Because, as we all know from life, everything always happens at once.

For those early church disciples who apprenticed and practiced to become “more” than “believers” but to become genuine “followers” of Jesus, the ceremony of baptism came on Easter morning. The Great Vigil is the first Easter service, and it is at that service historically that the candidates who completed their three-year apprenticeship with Jesus, were baptized–just as Jesus’ first disciples had been apprenticed by their Master for three years. The third celebration of Jesus rising from the grave during their apprenticeship, of Jesus conquering death and reigning victorious over the grave, was their Easter morning baptismal jubilation.

The earliest Christians used the language of “plunge, inundate, and immerse” when talking about baptism. These terms were often used in different ways in antiquity before the Christians begin to use it for baptism. It was used for drunkenness as in you are inundated with alcohol. It was also used of shipwrecks when they are finally plunged beneath the water.

Can you imagine what it was like for them, in that glow of gladness, to be “inundated” into the water, “plunged” into the depths to die to self and rise to new life, truly forgiven and truly blessed. As they rose out of the water, it was the person who was most responsible for introducing them to Christ who would whisper in their ears the secret sacred prayer disciples of Jesus were known for. You would only hear as much of “The Disciples’ Prayer” as your mentor thought you could handle. The words were so revolutionary. Each word a gift. Each word a world of revelation in itself. Maybe all you got whispered was “Our Father, who art in heaven.” Or maybe your three-year apprenticeship had been so stellar that you heard “Our Father, who art in heaven, hallowed by thy name. Thy kingdom come, thy will be done on earth as it is in heaven.”

But however much of the prayer you received as your baptismal gift, you were sent on your way into the world to be fully “Christians” –“little Christ” set loose on the world to turn it upside down. Like Jesus did.