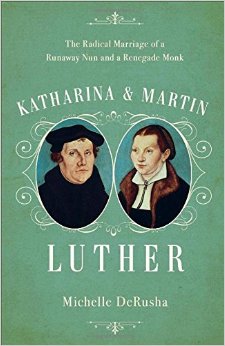

Katharina and Martin:

The Radical Marriage of a Runaway Nun and a Renegade Monk

by Michelle DeRusha

–Review by Teri Hyrkas

This year will mark the 500th Anniversary of the start of the Protestant Reformation, begun by Martin Luther in Wittenberg, Germany on October 31, 1517. Of the numerous church and societal changes credited to Luther, there is one that is so pervasive that it could be overlooked: marriage reform. In her book, Katharina and Martin: The Radical Marriage of a Runaway Nun and a Renegade Monk (Baker Books, 2017), author Michelle DeRusha explains that during the Reformation, Luther pressed steadily for revision of German ecclesiastical and civil laws governing matrimony. During this time of change, Luther surrendered to pressure from his closest friends who called on him to live out in his own life what he expected to see done in the lives of others, and Luther himself got married. Luther’s marriage was judged to be a radical undertaking for a man who was previously a monk, but his choice of a wife was profoundly revolutionary as well: the woman who became Luther’s wife was the noblewoman and former nun, Katharina Bora.

In the well researched Katharina and Martin, DeRusha trains her attention on and forms her narrative around Bora. The author acknowledges in the first pages of her book that there is not much information available on Katharina. What is known about Katharina’s early life, says DeRusha, is that at age six she was placed in a cloistered school one hundred miles from her home, then four years later she was transferred by her father to a convent where she was to begin her training as a nun. Katharina remained in the convent for close to fifteen years.

In 1523, Bora and ten other nuns wrote a letter to Martin Luther in which they stated their desire to flee the convent, and asked for Luther’s help to accomplish this risky feat. Luther did help Katharina and the other cloistered women escape from a convent in Nimbschen. In the perilous nighttime flight, the nuns were transported by wagon to the city of Torgau. The next day they walked to Wittenberg, where the escapees found lodging and protection in the Black Cloister, not far from Luther’s lodgings.

Soon after, the runaways were given chambers in various households close by. DeRusha notes that their escape from the convent was not the end of the women’s hardships. Most of their families would not, or could not, receive the women back; the townsfolk were suspicious of them, and they had no employable skills. DeRusha writes, “[Marriage] was the best and most viable option for the former nuns, and for a time, Luther took on the role of Wittenberg’s matchmaker, writing letters to potential suitors and helping to arrange engagements for the nuns who hadn’t been taken in by their families.”

Nearly two years after her escape, Katharina was the only former nun who had no plans for the future. Because her choices were very few, DeRusha tells us, Katharina boldly made it known that there were two men that she would accept as a husband: Nickolaus von Amsdorf (a close friend of Luther’s), or Luther himself. Eventually Luther agreed to marry Katharina. DeRusha writes: “The question is, why did Luther say yes?” The remainder of the book is given over to an investigation of this important question and an exploration of the couple’s wedded years.

DeRusha’s tale of Katharina and Luther is a touching story that offers some enlightening peeks into the unique difficulties of their marriage; for instance, after their nuptials, slanderous rumors and controversies continuously surrounded the couple’s lives, and Luther had a price on his head all the years of their marriage, which added to Katharina’s anxieties every time Luther traveled. Although the records show that their marriage was filled with hardship, in particular the deaths of two daughters, their personal letters also reveal great tenderness between Katharina and Luther. The couple did not marry for romantic reasons; however their correspondence contains declarations of love and concern for each other and their children.

A troubling episode in the story of Katharina involves the period after Luther’s death from illness. Sadly, the great respect awarded to Luther for his many accomplishments during his lifetime did not translate to practical help for his widow and children after his death. Katharina and her children faced extreme financial hardship after Luther died, and were compelled to move from place to place because of debt. Katharina was eventually forced to beg for financial assistance from family friends.

Michelle DeRusha has provided a valuable perspective on marriage in her very enjoyable Katharina and Martin: The Radical Marriage of a Runaway Nun and a Renegade Monk. There is no doubt that, as DeRusha says,”[Katharina Bora’s] marriage to Martin Luther and her role in helping to define clerical marriages and Protestant family life makes Katharina an important contributor to the Reformation….” But as well, DeRusha’s portrayal of the couple’s ability to grow from simple respect for one another to a deep and loving marriage relationship has the power to touch hearts today. Katharina and Martin would be a great book for history buffs, a couples book club, or even a marriage enrichment class.

Trackbacks/Pingbacks