Blue Mind

The Surprising Science That Shows How Being Near, In,

On or Under Water Can Make You Happier,

Healthier, More Connected and Better At What You Do

by Wallace Nichols

The mantra “In-the-name-of-Science” has fostered many kinds of research over the years, but recently it seems like the specialty of neuroscience is dominating the research sector. The book Blue Mind by Wallace Nichols, published by Little, Brown and Company in 2014, is one that seeks to establish the interest of neuroscience in the all-pervasive element of water.

The phrase “Blue Mind,” a term developed by Nichols, does not have a scientific definition. “Blue Mind” is best understood as a rather flexible, dare I say fluid, term that reflects a broad awareness of and regard for water. It also refers to the myriad of connections that humans have forged with water, and is identified with how profoundly people are connected to it in daily life. The very long subtitle of the book, “The Surprising Science That Shows How Being Near, In, On or Under Water Can Make You Happier, Healthier, More Connected and Better At What You Do,” hints at the many kinds of stories included in the book. It is fascinating to learn in Blue Mind how water touches every part of life, including the physical, social, financial, emotional, and the spiritual. Nichols, as a marine biologist and field research scientist, is certainly an expert in his field, but he is also personally under the spell of water as one who is an active swimmer, diver and surfer. In Blue Mind, Nichols seeks to bring the world of science and the human experience of water together:

“I came to believe that … stories (about people’s experiences around water) were critical to science because they help us make sense of the facts and put them in a context we can understand. It’s time to drop the old notions of separation between emotion and science — for ourselves and our future. Just as rivers join on their way to the ocean, to understand Blue Mind we need to draw together separate streams: analysis and affection; elation and experimentation; head and heart.”

Blue Mind is written in a manner which makes the various technical processes of tracking the way the brain works and the methods used to collect that data very readable for anyone. And even though Nichols quotes from a wide range of brain experts, scientists and medical professionals throughout his book, he doesn’t leave the non-scientist in a state of confusion with their technical jargon. Nichols also has helpful end-notes for those who desire to pursue more details about the people or studies mentioned.

One of the persistent questions in Blue Mind is this: “Why do we love water so much?” The short answer is that being around water seems to affect our emotions in positive ways, that is, for most of us, water makes us happy. We know this to be true anecdotally and subjectively. People frequently share how much they enjoy time spent at the lake, in a boat, fishing, swimming or simply walking on the beach. According to Nichols, until the 2000’s, scientific studies about happiness relied on study subjects’ ability to identify “happiness” when they felt it, and then accurately report it. Nichols writes, “While such self-reporting is critical to many sociological and psychological studies, for the past two decades PET and fMRI scans have given us greater insight into the neurobiology of happiness.” ‘Such studies make it clear that human emotions are not just fuzzy feelings but ‘real’ in an objective scientific sense, inasmuch as they produce measurable signals in reproducible experiments,’ writes Oxford-based science journalist Michael Gross. Today we can get a clearer picture of what happens in the brain when we happily take that walk on the beach,” say Nichols.

Nichols uses great care throughout Blue Mind to make a case for the positive benefits that water offers. Regrettably, he virtually ignores any negative feature of water, and as a result the stories in Blue Mind become somewhat repetitive and predictable. And yet, the book was worth reading because of the passion and concern about water that Nichols shares through it. Wallace J. Nichols loves water and wants to influence his readers to care about water, too. Wisely, Nichols understands this about human nature: “People won’t respond positively when we bore the heck out of them with facts. They won’t respond with action when we make them feel guilty or bad about themselves. Yet that is exactly what the environmental movement has been doing: scaring people, making them feel bad and overloading them with data.”

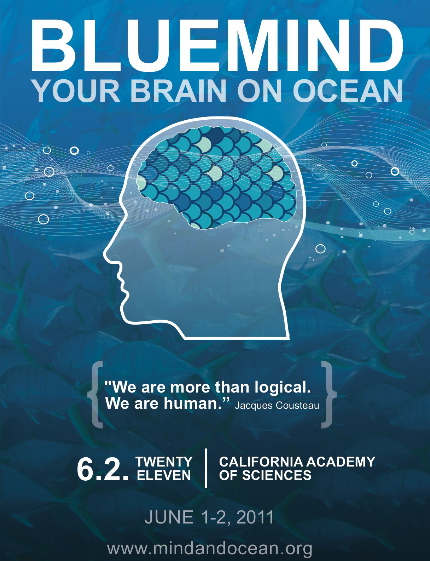

I believe this quote from the book from Luca Penati, managing director of Ogilvy and Mather, who spoke at the first Blue Mind conference in 2011, aids the reader in identifying the purpose of Nichols’ book: “We know from painful experience that the most potent facts and rational arguments for conservation have mostly fallen on deaf ears. Storytelling helps us to communicate the urgency of the (water) situation and the need for immediate action in a more powerful way. Storytelling is as old as history itself, and all great communicators have been brilliant storytellers. Now, neuroscience confirms that storytelling has unique power to change opinions and behavior.”

The storytelling in Blue Mind succeeds for the most part. I certainly applaud Nichols for his skillful exposition of many different scientific studies in support of his heartfelt concerns for and appreciation of water. (#Pulpit-prompt: preachers may find some inspiration in Blue Mind to do some image exegesis from scripture regarding water.) Nichols wants the readers of Blue Mind to develop, as he puts it, “a marine mindset,” but even more, I think Nichols wants all of us to learn to love water. As Jacque Cousteau said, “People protect what they love.” Nichols is very persuasive in Blue Mind that water and all it represents, needs our attention and protection.

thyrkas