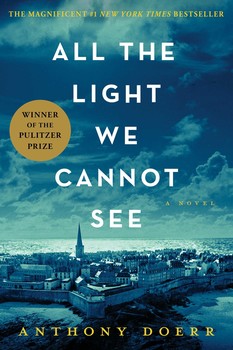

All the Light We Cannot See

by Anthony Doerr

A dazzling book, All the Light We Cannot See by Anthony Doerr, published by Scribner in 2014, concerns a subject that would not necessarily bring the word “dazzling” to mind — war. World War II and the Holocaust are the underlayment of the novel, and upon this is shaped the story of the parallel lives of two young people — a blind French girl and a orphaned German boy. These two youngsters, who grow up during World War II and are molded by the extraordinary pressures of the time in which they live, also learn about and engage in an emerging technology of the time: radio. The title, All the Light We Cannot See, was inspired by the electromagnetic spectrum which, among other things, includes radio waves and visible light waves. Both sound and sight are dominant themes throughout the book.

All the Light We Cannot See won the 2015 Pulitzer prize for fiction. It is a love story, but not in the typical boy-meets-girl fashion. The love story has more to do with family love, although the main characters do seem to be on a course to meet at some point in time, and through this potential intersection of their lives, Doerr adds a level of romantic suspense to the novel. The conduit for the possible meeting of the main characters is the power – emotional, political and technological power – of the radio.

From the beginning, the style of All the Light We Cannot See is cliché breaking. In particular, Doerr’s writing is imaginative and surprising, which de-familiarizes the otherwise well-known World War II setting, changing it from predictable to fascinating. Also, the structure of the book is non-typical; the chapters are short, sometimes less than a page long. They alternate equally between the story of the blind, courageous Marie-Laure Le Blanc and the bright and determined Werner Pfenning. Doerr deftly brings the reader into the relationships, interests, and problems that surround the two young people, but he also crafts a fairytale type of setting at times through the account of the conveyance and hiding of a very rare, valuable museum artifact, as well as the ongoing story of Jules’ Verne’s Twenty Thousand Leagues Under the Sea.

The short, polished chapters in All the Light We Cannot See explore the youngsters’ lives as they grow up in wartime; one of them is learning the ways of the aggressor, the other is becoming skilled in resistance. Marie-Laure and Werner make agonizingly difficult moral choices in their young lives — choices that require clear vision, internal strength, and maturity beyond their years. Because we see Werner’s struggles as an orphan, it is hard to be unsympathetic toward him, even as he is becoming indoctrinated in Nazi ways. Marie-Laure, despite the physical limitations of blindness and the conflict in her home about becoming involved in resistance activities, sees the desperation of the wartime situation clearly and chooses a life of risk-taking over one of supposed safety. How Marie-Laure achieves her desired goal and how Werner gains awareness of the barbarity of National Socialism is an intense and emotional journey, and one that insists that the reader pay attention and remain involved in the story to the end.

Doerr’s writing in All the Light We Cannot See startlingly beautiful. Below are some examples:

“At the lowest tides, the barnacled ribs of a thousand shipwrecks stick out above the sea.”

“Is it any wonder, asks the radio, that courage, confidence, and optimism in growing measure fill the German people? Is not the flame of a new faith rising from this sacrificial readiness?”

“Up and down the lanes, the last unevacuated townspeople wake, groan, sigh. Spinsters, prostitutes, men over sixty. Procrastinators, collaborators, disbelievers, drunks. Nuns of every order. The poor. The stubborn. The blind.”

“They start up the length of the rue Cuvier. A trio of airborne ducks threads toward them, flapping their wings in synchrony, making for the Seine, and as the birds rush overhead, she imagines she can feel the light settling over their wings, striking each individual feather.”

In an interview with Marcia Franklin, moderator for the Idaho Public Television program Dialogue which was recorded on July 16th, 2014, Doerr spoke about the challenge of writing for the character Marie-Laure. Because she is blind, Doerr was forced to write her story as if he too were blind. He said it forced him to experience life “through the other senses,” and was a difficult but helpful writing discipline. Here is an example of how Doerr painted life through the blind eyes of Marie-Laure:

“Color—that’s another thing people don’t expect. In her imagination, in her dreams, everything has color. The museum buildings are beige, chestnut, hazel. Its scientists are lilac and lemon yellow and fox brown. Piano chords loll in the speaker of the wireless in the guard station, projecting rich blacks and complicated blues down the hall toward the key pound. Church bells send arcs of bronze careening off the windows. Bees are silver; pigeons are ginger and auburn and occasionally golden. The huge cypress trees she and her father pass on their morning walk are shimmering kaleidoscopes, each needle a polygon of light.”

In a podcast of a recent writers’ workshop offered by Tin House magazine, Doerr encouraged writers to “re-see” the world around them, and spoke about the need for authors to de-familiarize the reader with the subject of their writing. He warned that writers’ and readers’ perceptions of persons, places and things become automatic, and that it is good to add friction to stories by making predictable things “alien.” This makes what is being described fresh and appealing to the reader. The writing skill of de-familiarization is used very effectively by Doerr throughout All the Light We Cannot See. (#Pulpit-prompt: De-familiarization and many other writing/preaching techniques are spilled out in Leonard Sweet’s 2014 cutting-edge book on preaching called “Giving Blood,” published by Zondervan. Also, master sermons, story sermons and other resources for preachers are available for use here at www.preachthestory.com.)

Doerr brings All the Light We Cannot See to a close in the year 2014. Again from the Dialogue interview of July 6th, 2014, Doerr commented on the conclusion of his book. He told Ms. Franklin that he wanted to end the book by bringing the story into the present time because, “Every day the world loses people for whom World War II is a memory.”

There are many reasons to read All the Light We Cannot See; here are a few:

- The story is told from the perspective of youngsters, which allows the reader the freedom to walk through the characters’ experiences with the mind of a child and therefore be less entrenched in his/her own opinions.

- Doerr’s abilty as a storyteller makes it possible to sympathize, however briefly, with bad decisions made by desperate people.

- The standard definitions of what makes a person strong, clear sighted, and powerful are challenged.

- The conflict inherent in the power of technology is made personal.

- Readers re-see and remember the horrific times of World War II through the stunning language of Anthony Doerr.

I hope you will chose to read All the Light We Cannot See.